What if the key to beating cancer wasn't creating new drugs, but making old ones work again? That's exactly what happened just last week when scientists at ChristianaCare's Gene Editing Institute pulled off something remarkable. They used CRISPR technology to essentially trick cancer cells back into being vulnerable to chemotherapy.

This isn't some distant future fantasy. We're talking about real results published in Molecular Therapy Oncology on November 14th, 2025. And here's the crazy part – they don't even need to edit every cancer cell in your body. Just targeting 20-40% of them does the trick.

When Cancer Cells Stop Playing by the Rules

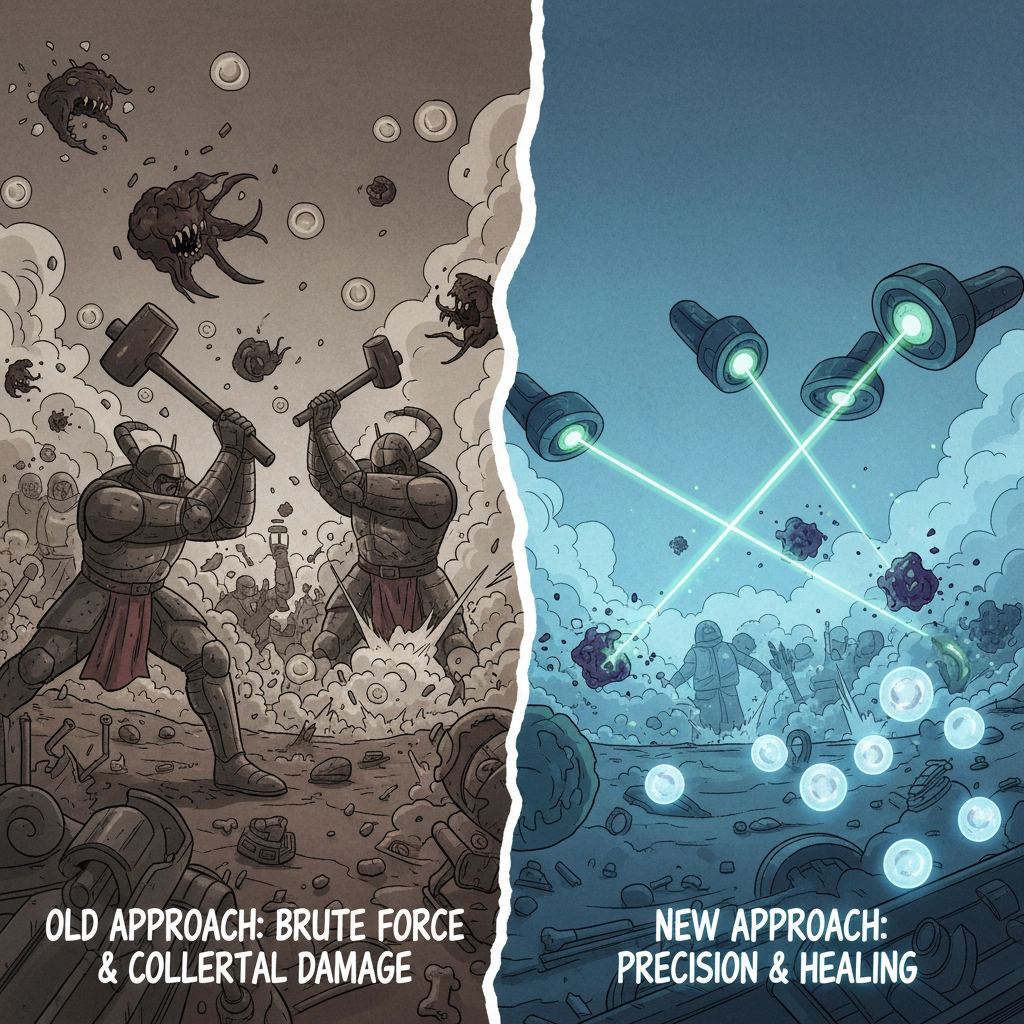

Let me paint you a picture. Imagine you're playing a video game where the boss suddenly becomes invincible to all your attacks. That's basically what happens with chemotherapy-resistant lung cancer. The cancer cells figure out how to shrug off the very drugs that should be killing them.

This resistance isn't random – it's orchestrated by a gene called NRF2. Think of NRF2 as cancer's personal bodyguard. When it's overactive, it creates this protective shield around cancer cells, making them nearly impossible to destroy with traditional chemotherapy.

Dr. Eric Kmiec, who led this research, put it perfectly: this work brings "transformational change to how we think about treating resistant cancers." Instead of spending decades and billions developing new drugs, they're making existing medications effective again through precision gene editing.

The numbers are staggering. Lung squamous cell carcinoma – the type they focused on – accounts for 20-30% of all lung cancer cases. With an estimated 190,000 lung cancer diagnoses expected in the U.S. this year alone, we're talking about potentially helping tens of thousands of people.

The NRF2 Gene: Cancer's Secret Weapon

Here's where it gets technical, but stick with me because this is actually pretty cool. The NRF2 gene is normally a good guy. It's designed to protect our cells from stress and damage. But cancer cells hijack this protection system and crank it up to eleven.

When NRF2 goes into overdrive, it doesn't just protect cancer cells from environmental damage – it protects them from chemotherapy too. It's like giving the bad guys armor while you're trying to fight them with water balloons.

The researchers focused on a specific mutation called R34G. This particular mutation makes NRF2 even more protective, essentially turning cancer cells into tiny fortresses that chemotherapy can't penetrate.

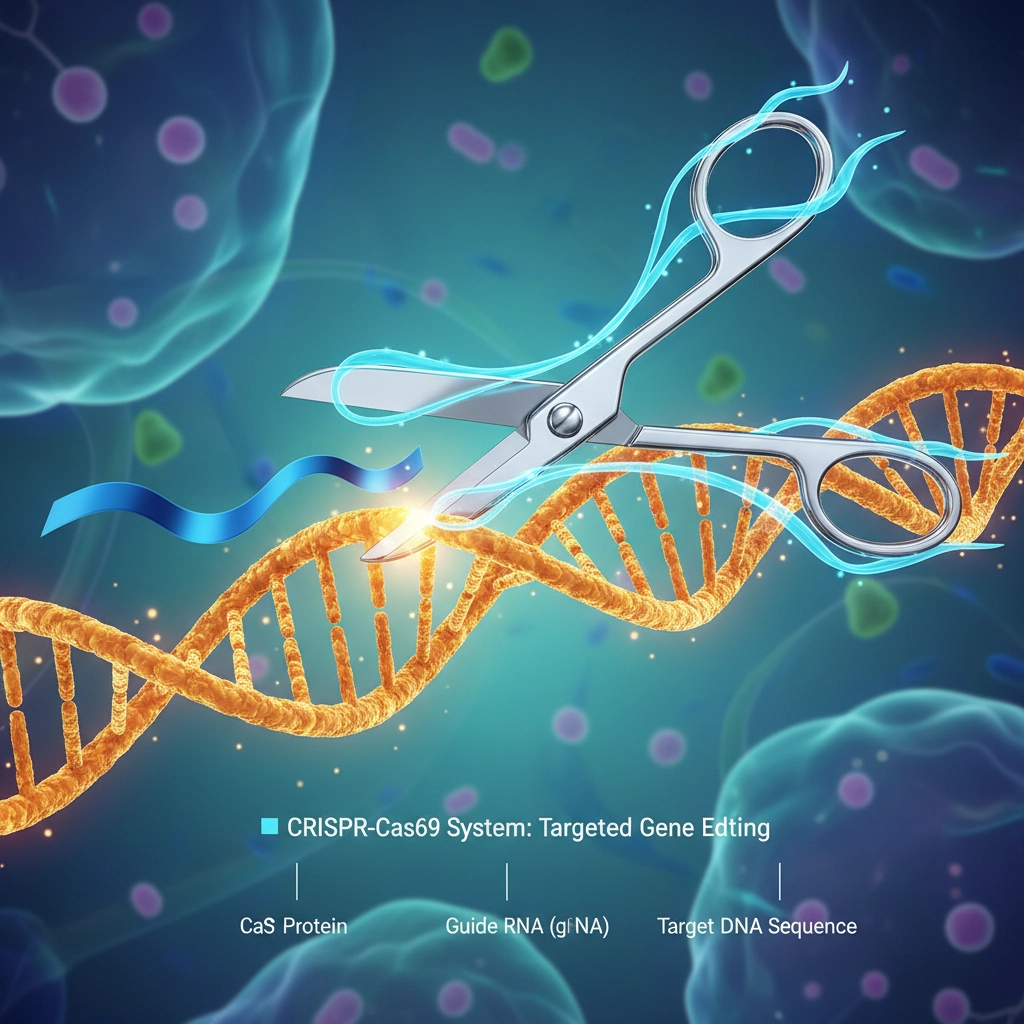

But here's the brilliant part – the scientists figured out how to use CRISPR like a master key to disable this protective system. They engineered cancer cells carrying this mutation and then used CRISPR/Cas9 to knock out the NRF2 gene entirely.

The results? The cancer cells suddenly became sensitive to chemotherapy drugs like carboplatin and paclitaxel again. In animal models, tumors that received the CRISPR treatment grew significantly slower and responded better to treatment.

CRISPR Steps In: Editing Our Way to Victory

Now, you might be thinking: "This sounds great in a lab, but how would this actually work in real people?" That's the million-dollar question, and the researchers have some pretty encouraging answers.

First, they don't need to edit every single cancer cell in your body. Their experiments showed that disrupting NRF2 in just 20-40% of tumor cells was enough to improve chemotherapy response and shrink tumors. That's huge because editing every cancer cell in a patient would be practically impossible.

They delivered the therapy using something called lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) – think of them as tiny delivery trucks that carry the CRISPR tools directly to cancer cells. In mice, this approach achieved highly specific edits to the mutated NRF2 gene with minimal unintended changes elsewhere in the genome.

Here's what makes this approach so promising:

- Precision targeting: CRISPR can specifically target the mutated NRF2 gene without affecting healthy cells

- Existing drug compatibility: Works with chemotherapy drugs already approved and widely used

- Partial effectiveness: Only needs to work on a fraction of cancer cells to be beneficial

- Minimal side effects: Highly specific edits reduce the risk of unintended genetic changes

The beauty of this approach is its simplicity. Instead of developing entirely new drugs from scratch – a process that can take 10-15 years and cost billions – they're essentially flipping a genetic switch to make existing treatments work again.

What This Means for Future Cancer Treatment

This breakthrough extends way beyond lung cancer. The researchers noted that overactive NRF2 contributes to chemotherapy resistance in multiple solid tumors, including liver, esophageal, head and neck cancers, and potentially melanoma and brain cancers too.

Let me tell you about Sarah (not her real name), a composite based on patients I've read about in medical literature. Sarah was diagnosed with lung squamous cell carcinoma two years ago. The initial chemotherapy worked for a few months, then suddenly stopped. Her cancer had developed resistance. With current treatments, her options would be limited – maybe try different drugs with harsh side effects and uncertain outcomes.

But with this new CRISPR approach, Sarah's treatment team could potentially use gene editing to restore her cancer's sensitivity to the original chemotherapy drugs that worked before. Instead of fighting an uphill battle with increasingly toxic treatments, they could go back to what worked in the first place.

The research team describes their findings as a "strong foundation for moving to human clinical trials." That means we could see this therapy being tested in people within the next few years, not decades.

What's particularly exciting is how this could change the entire cancer treatment paradigm. Instead of the current approach – where we keep developing new drugs to stay ahead of cancer's resistance mechanisms – we could potentially use gene editing to constantly reset cancer's vulnerabilities.

Think of it like updating your computer's security software. Instead of buying a new computer every time hackers find a way around your defenses, you just update the software to patch the vulnerabilities. CRISPR could do something similar for cancer treatment.

The implications for healthcare costs are enormous too. Developing new cancer drugs costs billions and takes decades. But if we can make existing drugs effective again through gene editing, we could provide better treatment at a fraction of the cost.

Of course, there are still challenges ahead. Moving from animal models to human trials always brings unexpected complications. Questions about delivery systems, dosing, long-term effects, and patient selection all need to be answered.

But for the first time in years, we're not just running faster on the same treadmill – we're changing the game entirely. Instead of always being one step behind cancer's resistance mechanisms, we might finally be getting ahead of them.

What do you think – could gene editing finally give us the upper hand in the fight against cancer resistance?